An 11-page PDF can trigger political change in a country of 54 million people. This is one such case. Deeply in debt and in talks with the IMF, Kenya announced at the end of June an economic plan that included tax hikes aimed at reducing the government’s budget deficit. Everything from bread to mobile money transfers was taxed. With a population already struggling due to rising food prices, the plan won favour with investors but was rejected by the Kenyan public. Protests erupted, leading to at least 39 deaths, and Parliament was stormed by some demonstrators. Ultimately, President William Ruto scrapped the law.

It was a demonstration of democratic vitality, though a blow for investors, as an emerging markets analyst remarked to Bloomberg. Just days after the measures were withdrawn, credit rating agency Moody’s downgraded Kenya’s credit rating. This was a clear signal: Kenya, which borrowed at over 10% interest in February to repay a bond maturing in June, will now face even greater difficulty accessing private markets. Going forward, any similar borrowing is likely to come with interest rates exceeding 10%. Under these circumstances, securing IMF financing – which offers lower interest rates – and accepting its terms becomes almost unavoidable.

This is the dilemma faced by many African nations that borrow in dollars on the private market. When interest rates rise at the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, the financing window closes, leaving them trapped between private creditors and the IMF: they must either take on debt at cripplingly high rates or agree to a structural adjustment programme. They cannot stop borrowing dollars, as these are needed to pay for imports like food and fuel, without which no society can function.

As long as the country can still secure loans, it can refinance its debt shortly before it matures – borrowing $100 to pay off the $100 owed – with only the interest changing. The problem comes when that financing window closes or loans become too expensive, causing interest payments to consume a significant portion of the national budget each year. In countries like Kenya, Angola, Malawi, Uganda, and Ghana, more than 20% of government revenue is spent on debt interest. Two countries exceed 30% (Zambia and Nigeria), while Egypt has already surpassed 40%. In May, economist Carlos Lopes from Guinea-Bissau wrote that African countries would struggle to resolve their debt crises within a system “rigged against them.”

Financing as a Starting Point

At the end of March, Senegal’s new government, led by Bassirou Diomaye Faye, completed one of the most remarkable political stories in recent memory. Faye, who had been imprisoned, went from jail to a first-round electoral victory in just 11 days. His main backer, the popular Ousmane Sonko, was also released from prison and played a pivotal role in defeating Amadou Ba, the protégé of outgoing president Macky Sall. Their promises resonated particularly well with Senegal’s youth. For now, however, the new government’s initial economic policies have maintained continuity with the previous administration. The IMF welcomed the Faye government’s commitment to the existing reform programme and its intention to continue along the path of ‘fiscal consolidation’. The confidence of financial markets in the new government was evident in the sale of eurobonds worth $750 million, at an interest rate of 7.75%, with a seven-year term. With significant debt maturities looming in 2026, the more radical promises of the campaign – such as exiting the CFA franc or renegotiating natural resource contracts with foreign companies – seem like distant echoes. With a perpetual trade deficit, Senegal has little room to reduce its dependence on lenders, who consequently set the limits of its policies.

The new administration could gain breathing room thanks to its growing diaspora. Migration is an essential economic factor for Senegal, representing 10% of GDP, with Senegalese abroad contributing nearly $3 billion to the national economy in 2023. In the vast majority of cases, these are sporadic remittances that help with food purchases and paying utility bills. During the pandemic, this influx of cash was a lifeline, offsetting the collapse of tourism; more recently, it has helped cushion the blow of rising food prices following the war in Ukraine. Over the years, this diaspora has also begun to make its political voice heard. Beyond sending money, they want a say in the future of their country. They were instrumental in financially supporting the opposition party that ultimately won the presidency. In few African countries is there such alignment between the diaspora and the government as in Senegal. In this context, diaspora bonds could be an attractive option for securing more affordable financing – in dollars or euros. This way, the diaspora could transform their regular contributions into a more ambitious investment tool.

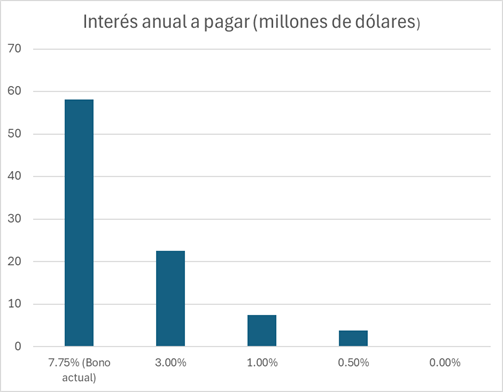

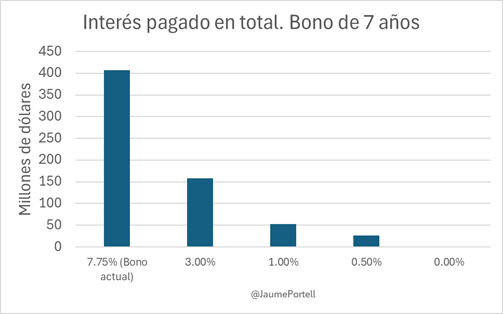

Let’s consider Senegal’s recent eurobond issuance. At 7.75%, the country will pay roughly $58 million in annual interest over seven years. In total, it will have paid over $400 million just to borrow $750 million. A diaspora bond is an instrument previously used by countries like Israel and India, where patriotic sentiment among investors allows them to secure more favourable interest rates, and in some cases, it is employed during times of restricted access to capital – precisely the situation many African nations now find themselves in. If Senegal could sell a $750 million bond to its diaspora at a 1% interest rate, it would save over $50 million annually just in interest. That’s $50 million a year that could be spent on schools, hospitals, infrastructure, or support for farmers. Each year. Increasing the amount of food produced domestically would also reduce the import bill for products like rice ($657 million in 2022), maize ($100 million), potatoes ($32 million), and onions ($113 million).

Savings on the import bill could be reinvested into Senegal’s economy, funding machinery imports to boost agricultural productivity or enhancing energy independence. As it stands on the verge of becoming a producer of oil and gas, Senegal will soon have a new revenue stream that, under the current structure, would largely go towards paying the growing interest on its debt. These high interest payments help maintain the country’s economic structure: with the burden of annual debt payments, the country can scarcely fund an industrialisation project. Senegal continues to export raw peanuts, cultivated on a third of its farmland, just as it did in colonial times. Reducing the interest bill could open up space to expand social protection, increase investment, and support a more resource-focused agricultural policy.

Short-term Challenges vs. Long-term Gains

Reducing remittances to families would be a major shift. Fewer remittances would mean less consumption and fewer customers for certain businesses, a shock to the local economy. This is the key drawback of a potential diaspora bond, but the medium-term benefits would be considerable: increased agricultural productivity – supported by cheaper fertilisers for farmers – would boost food availability, cutting the amount spent on food imports, currently covered by remittances. If Senegal could gradually replace its 7% interest bond portfolio with bonds at 1%, the structural reduction in interest payments would free up funds to support families during this transition. External debt interest payments are one of Senegal’s largest government expenditures. In 2023, according to UNCTAD, Senegal spent 12.5% of its government revenue on interest payments. By issuing diaspora bonds and investing in local agriculture, Senegal could be on the path to reducing this burden and redirecting funds to its people. Unlike bond issuances, which are subject to the whims of international markets and interest rates set by rich-country central banks, the diaspora sends money to Senegal every year, no matter what. These remittances already amount to twice the international aid the country receives. If the money exists, why not use it differently?

Author: Jaume Portell.